The term teleconnection has long been defined as interactions between behaviors separated by geographical distances. Using Google Scholar, the first consistent use in a climate context was by De Geer in the 1920’s [1]. He astutely contrasted the term teleconnection with telecorrelation, with the implication being that the latter describes a situation where two behaviors are simply correlated through some common-mode mechanism — in the case that De Geer describes, the self-registration of the annual solar signal with respect to two geographically displaced sedimentation features.

As an alternate analogy, the hibernation of groundhogs and black bears isn’t due to some teleconnection between the two species but simply a correlation due to the onset of winter. The timing of cold weather is the common-mode mechanism that connects the two behaviors. This may seem obvious enough that the annual cycle should and often does serve as the null hypothesis for ascertaining correlations of climate data against behavioral models.

Yet, this distinction seems to have been lost over the years, as one will often find papers hypothesizing that one climate behavior is influencing another geographically distant behavior via a physical teleconnection (see e.g. [2]). This has become an increasingly trendy viewpoint since the GWPF advisor A.A. Tsonis added the term network to indicate that behaviors may contain linkages between multiple nodes, and that the seeming complexity of individual behavior is only discovered by decoding the individual teleconnections [3].

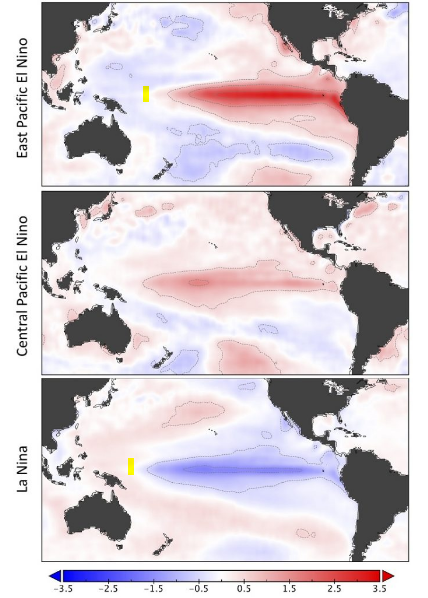

That’s acceptable as a theory, but in practice, it’s still important to consider the possible common-mode mechanisms that may be involved. In this post we will look at a possible common-mode mechanisms between the atmospheric behavior of QBO (see Chapter 11 in the book) and the oceanic behavior of ENSO (see Chapter 12). As reference [3] suggests, this may be a physical teleconnection, but the following analysis shows how a common-mode forcing may be much more likely.

Continue reading